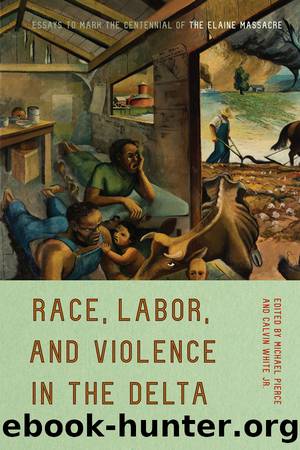

Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta by Race Labor & Violence in the Delta. Essays To Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre (2022)

Author:Race, Labor & Violence in the Delta. Essays To Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre (2022)

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781610757751

Publisher: University of Arkansas Press

CHAPTER 8

Sweet Willie Wineâs 1969 Walk against Fear

Black Activism and White Response in East Arkansas Fifty Years after the Elaine Massacre

JOHN A. KIRK

FOR FIVE DAYS IN AUGUST 1969, Lance Watson (alias Sweet Willie Wine), the leader of Memphis Black power group the Invaders, led a âwalk against fearâ across east Arkansas. The walk became an iconic episode in the stateâs civil rights history and the stuff of local folklore. It even inspired Arkansas-born poet C. D. Wrightâs acclaimed 2010 long-form poem One with Others [a little book of her days].1 Watsonâs walk echoed an earlier protest by James Meredith, who integrated the University of Mississippi in Oxford amid great controversy and conflict in 1962.2 In 1966, Meredith set off on a one-man âmarch against fearâ across rural Mississippi from Memphis to Jackson. Soon after setting off, Meredith was shot and wounded. Major national civil rights organizations continued the march while Meredith lay in his hospital bed. The march is perhaps best remembered for Stokely Carmichael, chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, popularizing the slogan of âBlack powerâ that quickly became the clarion call for a new Black youth movement.3

This essay explores the significance of Watsonâs walk against fear by using that demonstration as a counterpoint to compare with the events that unfolded during the Elaine Massacre fifty years earlier.4 It examines what those two civil rights episodes from different eras tell us about the continuities and discontinuities in Black activism and white responses to it. The two episodes point toward a continuity in Black activism and assertiveness, while illustrating a fundamental discontinuity in white responses. They suggest that white mob violence steadily declined in east Arkansas in the postâWorld War II era to be replaced by a reliance on law enforcement authorities to police the color line.

There is a relative dearth of works examining and theorizing the demise of white mob violence in the postâWorld War II South. Most surveys chart developments in the first half of the twentieth century, a literature that has flourished and expanded in recent years.5 Although there have been numerous accounts of individual episodes of white mob violence in the second half of the twentieth century, the literature for this period lacks a coherent and comprehensive survey that assesses how and why its role changed during that era, and why overall it declined. There is, for example, no equivalent to Herbert Shapiroâs bold, imaginative, and provocative study White Violence and Black Response: From Reconstruction to Montgomery, which provides an overview of racial violence from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries.6

Two scholars have provided notable tentative theses about the decline in white mob violence in the postwar era. For constitutional historian Michael R. Belknap, writing in Federal Law and Southern Order: Racial Violence and Constitutional Conflict in the Post-Brown South, the mid- to late 1960s were a pivotal moment that witnessed a sharp decline in such violence in the South. Belknap identifies the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi, which saw an âorgy of burning, bombing, beating and killingâ of civil rights targets, as the turning point.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Americas | African Americans |

| Civil War | Colonial Period |

| Immigrants | Revolution & Founding |

| State & Local |

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(2696)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2446)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(1967)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(1850)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(1748)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(1725)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(1668)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1626)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1619)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(1602)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1514)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(1512)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1420)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1346)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1343)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1343)

Decision Points by George W. Bush(1256)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1244)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1229)